Behringer has announced the release of its first analog synthesizer plug-in, which is also free! There is a lot to write about because it has the same structure as Ableton Analog. And we compared them. With a number of programming tricks.

Announced at a price of $99, the Behringer Vintage virtual instrument is now completely free by going through Behringer's site. Again, there was initial confusion: released a few days ago but not yet available, the Vintage synth was made by Stefano D'angelo, whom we know from his prolific activity with his company Orastron. This fact is enough for us to bring all our attention to Vintage, for D'Angelo is a well-known developer in the environment (see his previous work with Arturia) and has fine ears.

Announced at a price of $99, the Behringer Vintage virtual instrument is now completely free by going through Behringer's site. Again, there was initial confusion: released a few days ago but not yet available, the Vintage synth was made by Stefano D'angelo, whom we know from his prolific activity with his company Orastron. This fact is enough for us to bring all our attention to Vintage, for D'Angelo is a well-known developer in the environment (see his previous work with Arturia) and has fine ears.

Ableton Analog, on the other hand, is an instrument included in the Live 12 Suite, born in the days of Live 9, or can be purchased as packs for 79 euros.

Behringer Vintage is virtually identical in structure and user interface to Ableton Live's Analog, made by AAS, which has always been dedicated to the best emulation of analog with its Ultra-Analog. Same operating logic, same parameters. You can safely use Analog's instruction manual to learn how to use Vintage! The manual provided by Behringer is rather useless. The differences are in sound and size. Analog has a greater tonal quality, with a more present and less subtle body than Vintage, which, however, has a large interface on its side that significantly improves ease of programming. Of the two, we prefer Vintage for programming, but for sound, we stay with Analog's results. Given the release of Vintage, we took the opportunity to focus our attention on those details that elude the general public but are essential to the success of an electronic sound.

Vintage vs. Analog

The names are hardly original, but if Behringer wanted to give its virtual synth a definition, it succeeded. So did Ableton to identify what sounds you get with Analog.

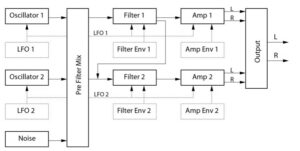

Behringer Vintage and Ableton Analog are virtual analog synths based on two VCOs, for each of which a single waveform can be chosen between sine, sawtooth, and square, the latter with PWM modulated by the LFO, two independent filters with Low Pass, Band Pass, High Pass, and Formant modes, and four envelopes, including two for as many VCAs and VCFs, with a choice of curve patterns between exponential and linear. The seven-mode drive VCF. There is a noise generator, Vibrato and Unison controls, Pan for the two VCOs and two independent LFOs. There are no chorus, delay or reverb effects, but there is full parameter assignment both on panel and for individual independent values within the display.

The two independent entries have the main controls above and below a large display. By clicking on the section, the display changes and shows all possible values related to that section. In other words, there are no submenus or hidden parameters. You can see everything right away. From here, we start our exploration of the more unusual parameters that make analog and vintage very interesting. We will mostly use the screenshots of Vintage because they are clearer.

Master

Not just Volume. The section includes Vibrato parameters (Delay, Attack, Error and Amount for control with the modulation wheel). Vibrato is controlled, in frequency and intensity, from its section on the right. We liked Error quite a bit! It really allows for those inaccuracies that are so analog! Master also reports general parameters, including the number of voices (mono to 32) of polyphony and for Unison (two or four). Here are at least three parameters that make a difference: Stretch, as a percentage, defines the pitch of the highest notes; Error introduces random pitch errors, and Delay (on Unison) is the trick to get those slightly offset openings between filters of different voice cards. A classic of Oberheim polyphonics, especially OBX (see special feature). Here we also see another detail of Vintage: some sections are activated only if the corresponding buttons are; for example, if the Vibrato and Unison sections are turned off, the corresponding parameters will not be displayed. And there is another detail, unfortunately: as soon as you use a knob of a section, the display changes. For example, changing the cutoff while programming Delay in Unison jumps to the related VCF page and we are forced to make a second pass over Master to get back to the starting point for the Delay parameter. Inconvenient!

LFO

The display shows LFO1 on the top line and LFO2 on the bottom line. Special features include the choice of Noise and Noise Ramp as modulator (they work like S&H) and offset, delay, and attack parameters that change things up. Attack, up to five seconds, allows for classic effects based on the choice of modulation source. By modulating the pitch (Pitch Mode LFO and Key) with a square wave and Attack at maximum, you get a descending and ascending pitch curve along with the introduction of modulation. Space effects from 1960s movies are here! Offset allows for even more play. LFO 1 is connected to VCO1 and LFO2 to VCO2. By assigning to the pitch, for example, a rectangular curve with different width and identical frequency of the LFOs but with the second one shifted with offset, you can arrive at almost arpeggio-like movements, the rhythm of which can be modified by frequency and offset. For LFOs, there is also synchronization to Tempo, in which case you can choose metronomic division with Rate. If you plan to play it to create rhythmic trends, remember to turn on Retrig (R) so that you have synchronized the start of the LFO cycle and do not go out of tempo. Vintage does not go below 10 Hz, unlike analog, which goes down to 0.1 Hz.

VCO

On the page, we find the pitch envelope: Pitch Envelope Initial actually indicates the pitch height, while Time is the time it takes to get to zero. Little trick: by placing opposite and minimum values of Pitch Initial for the two VCOs, you initially get almost a chorus effect, which goes out according to time. Liven up the attack. Selecting the square waveform, here we find the ability to set PWM modulation in intensity. Vintage includes an independent sub-oscillator for each VCO, the level of which can also be set. What about the sync? There is, and it is realized within the same VCO without sacrificing the second one. But there is one big problem. The classic sync sound that evolves over time is realized by modulating Ratio, but no parameter or modulator is assigned to this parameter. So here, it is necessary to assign a MIDI controller the Ratio value or automate it on the DAW.

The Modulated Sync trick

Although there are plenty of forums that say it cannot be done, the trick is there, and it takes advantage of the 100% modulated PWM waveform on the second VCO. It works on both Analog and Vintage. You need to select the square waveform, set width to 100%, turn on Sync, and put it above 30%, or wherever you like. At this point, you create a pitch envelope with the pitch envelope's initials and time. If you like, you can modulate the sync with a very low-frequency LFO (below 10 Hz) with a minimum value and key at 100%. Here you can see the differences between Vintage and Analog in the range of parameters that are not identical. It is not quite a classic sync, but it is very close. Analog's settings are in the opening image!

VCF

Amazing is the right word! Let's start with the filters: LPF at 12 and 24 dB/Oct, BPF at 6 and 12 dB/Oct, HPF at 12 and 24 dB/Oct, and Formant at 6 and 12 dB/Oct. There are hours of fun to be had, even with the formal one. The envelope has linear or exponential curves (pretty much to keep on exponential all the time), with attack, decay, sustain, sustain time and release times. A few parameters make it very flexible: a continuous loop with a choice of three segment intervals, negative modulation values for cutoff and resonance, very suitable for telluric and powerful basses, and finally, a drive parameter not listed in the manual but which changes everything. When it is on, with cutoff all closed, resonance at maximum, and positive envelope modulation, we are looking at the classic filter with the fairly Moog sound, but changing Drive is like having six other different filter patterns that tend to be softer, less punchy, and more open. Working for examples with a 12 eB LPF and Drive on Sym1, here is the sound of the classic TB303 appearing. And finally, two small parameters that indicate excellent research work: Legato allows you to run Vintage as a paraphonic on the filter, so all added notes will have the filter open at that moment. The second parameter is Free, which allows all envelope segments to be developed independently of note release. We will see that this function will be more interesting for VCA.

VCA

Much of what we have seen for the filter turns out to be present on the VCA page as well. The envelope is always an ADSR, with sustain time and the possibility of AD-R, ADS-R, and ADS-AR loops. Here again we find Legato and Free mode, which processes the entire envelope, including the release phase, but ignores the sustain time.The times of release and sustain are long enough (maximum 15 seconds) for long pads. We also find pan modulation with the LFO, velocity or envelope on this page. Amplitude modulation is realized by the LFO, even with negative values. Attack can be modulated by velocity.

Noise and controls

The last section has no display; you can send noise to both VCFs, balance them, and change the color of the noise. Only on Vintage, clicking on the icon next to Donate opens four controls, again mappable via MIDI, to control Brightness, Timbre, Time, and Movement.

Preset

Presented as the plug-in to get the classic vintage sounds, we expected a collection of classics. It wasn't. Knowing how to program an analog synth means that, in 90 percent of cases, you can imitate the sounds of any synth well. Behringer Vintage has a lot of cards to play, so the anticipation was high. Our tour was quite disappointing; a few Flexer, Simple Harp, Free Falling, Lunar Orbital, Soul Ripper, and VIP Utterances were saved. Some of these presets also have very different levels. Certainly, much better could have been done, considering the possibilities. This is different from the case with Ableton Analog, where all the presets have a distinct musical sense with some notable goodies. While Vintage struggles to create classic Prophet 5-type brass, Analog seems to have them in its DNA, and they are very smooth. Of the two, we always preferred Analog.

The verdict

Initially, we did not expect so much from Behringer Vintage. Free often rhymes with barely sufficient quality. We changed our minds as soon as we started programming it. Having thrown away the presets, we were able to quietly create leads, effects, pads, brass, strings, and synthetic basses with ease. The overall sound of Behringer Vintage is closer to a Roland than a Moog, often because of the presence of rich, high harmonics. It is not dissimilar to Roland, in fact. If you are looking for that open character typical of Roland, like the Juno 106, you will get satisfaction, but not the same dough. It is a synth that does not struggle to fit into the mix, thanks to its richly detailed timbre (watch out for the Brightness and Timbre control, which can change the result). On the other hand, we have Analog, which is more flexible and richer with better presets, with a timbre that is more American and less subtle than Vintage's, but never dull or musty, on the contrary. The difference can be heard, and it is no small thing. We personally prefer Analog if we were to look for something good and professional, but even with Behringer Vintage, we get useful results. Both have an attitude toward ultra-low frequencies, so much so that subwoofers shake. You have to know how to program them, however. In terms of speed of programming, Vintage wins hands down: everything is there where it needs to be and, above all, readable and attainable, but it requires knowledge of synths. In the case of analog, one has to learn the parameter positions because the window is always too small, at least for our eyes. Both are easy to automate with an external controller or synth, but Vintage wins because it has a dedicated button and everyone understands it.

Conclusions

It is a bit strange to see two virtual synthesizers have exactly the same parameters, but with two different parents. We are not getting into the details of how ethical it is to clone a plug-in with a better GUI. If Behringer is the emperor of hardware clones, as of today, we can say that it has also started with software. The results are not equal, but that does not mean that one is inferior to the other. For those who want to start programming, Vintage allows you to explore many parameters and features of analogs of the past. For those already working on Ableton Analog, Berhinger Vintage's GUI is unbeatable. About the sound, we prefer analog, but we would have no problem employing vintage in production. The choice is yours!

Pro

- Great versatility of filters

- Very convenient user interface on Vintage

- Easy automation and assignment to external controllers

- Negative envelope modulation

- Several parameters to emulate vintage faults

- Very musical Analog presets

Cons

- Fixed modulations

- No modulation source for sync between oscillators

- Presets on Vintage are very improvable

- Envelopes are not entirely percussive

Link to activate license and download software: Behringer Vintage